Chemical structures on stamps

Science is physics; everything else

is postage stamp collecting.

Ernest Rutherford

According to Rutherford, all chemistry (except, maybe, physical chemistry and quantum chemistry) is nothing else but stamp collecting. Of course, this is far from being true. One of the definition states that science is the method of exploring the surrounding reality (nature) by constructing the models of this reality. But this is what most chemists do – they construct models of atoms, molecules, colloid particles, complex systems, materials. They even do much more – they create new reality by synthesizing millions of new substances and materials which never existed in nature. That is why chemistry is definitely a science rather than only collecting data.

However, chemistry has some relation to stamp collecting as well. Combining chemistry and philately gives chemophilately – the pursuit of stamps related to chemistry. The total number of chemistry-related stamps issued since 1840 (when the first postal stamp was printed in Britain) is estimated as about 2000. Most of them are dedicated to important events, anniversaries, historic figures, various applications of chemistry in industry, medicine and so on. But the most interesting and beautiful stamps introduce the world of chemical structures – a very rich and diverse world. In this note, we consider the main types of chemical structures found on postal stamps.

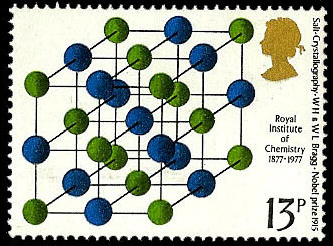

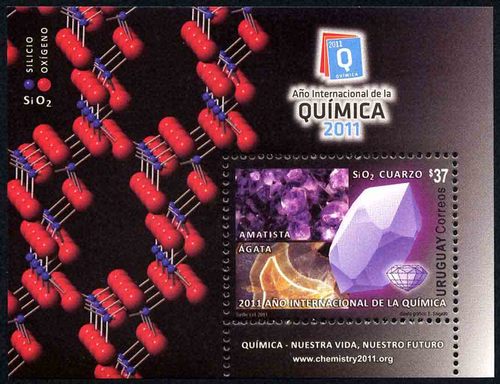

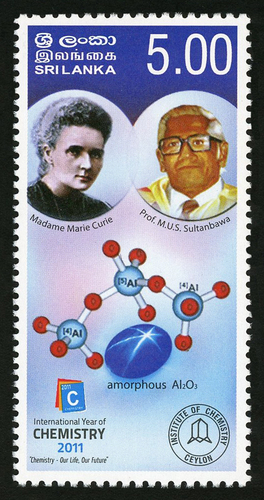

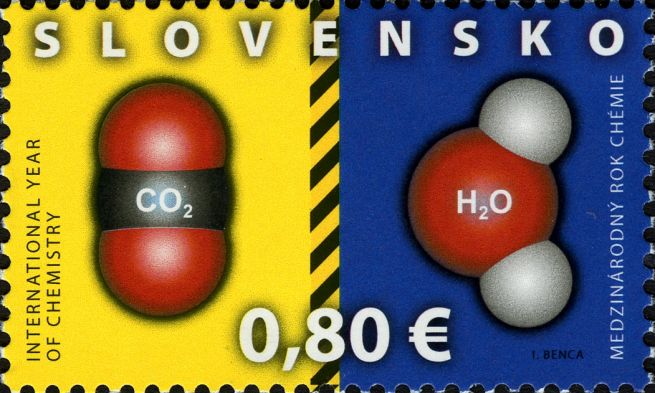

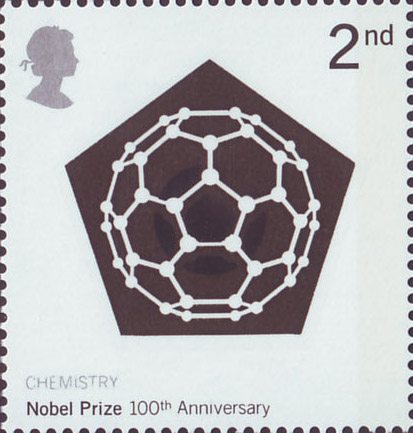

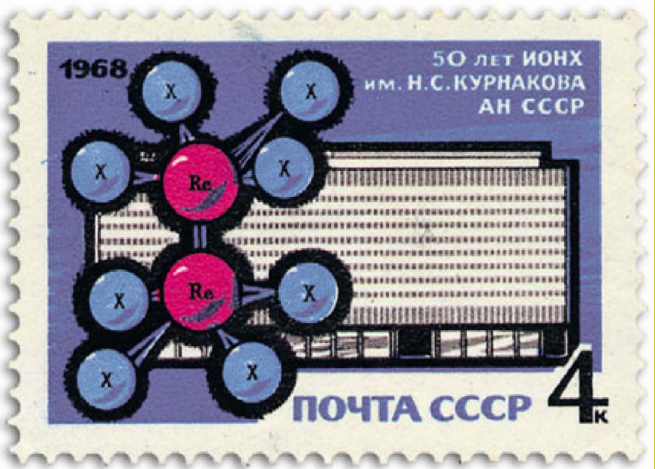

Inorganic substances are usually presented in chemophilately by crystal structures of ionic compounds (typically – NaCl, (1)) or minerals (2), (3) and various molecular structures – mainly of simple molecules (4). An interesting stamp (5) was issued in Great Britain in 2001 commemorating the centenary of Nobel Prize. One of the Nobel prizes in chemistry was awarded for the discovery of fullerenes – the new elementary form of carbon. The molecule of the most stable fullerene – С60 – is shown on the stamp. The stamp is heat-sensitive: upon light heating it turns pale. Another unusual structure – that of an inorganic ion Re2Cl82– with the metal-metal bond is presented on a Soviet stamp (6) celebrating the jubilee of the Institute of General and Inorganic Compounds (Moscow).

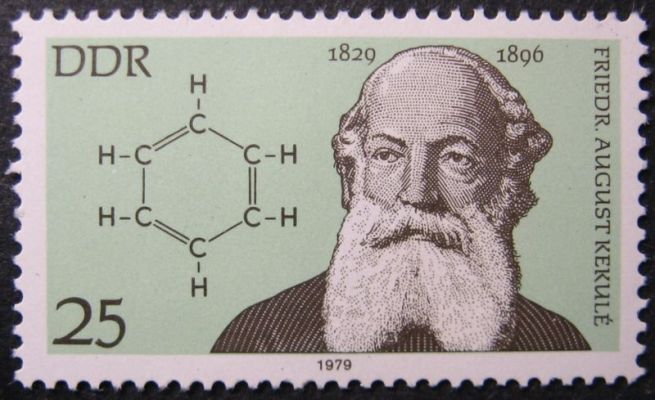

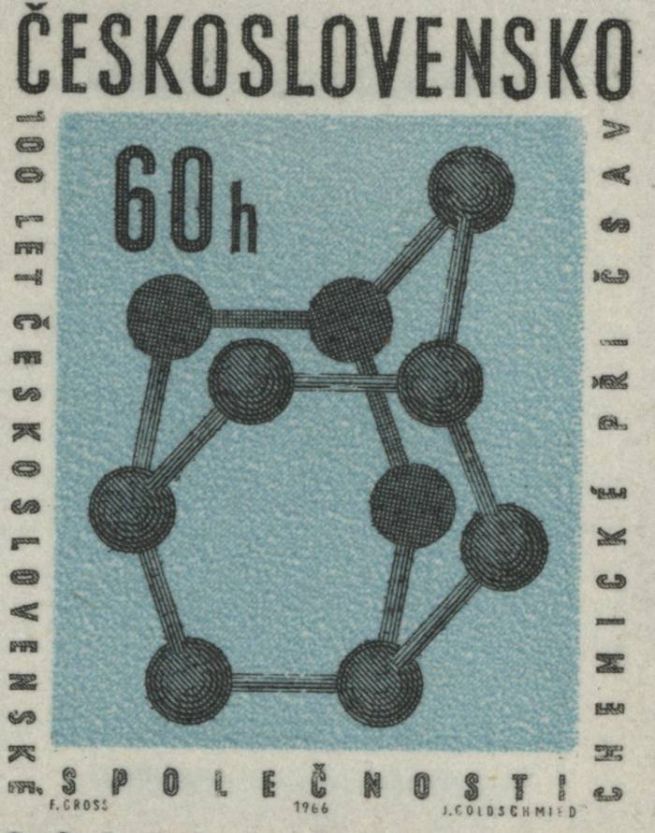

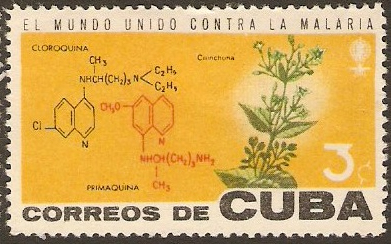

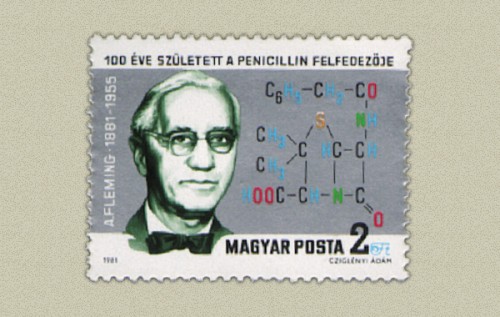

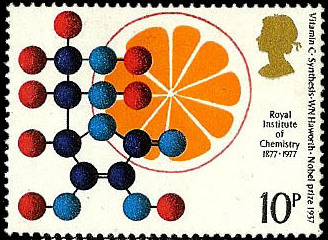

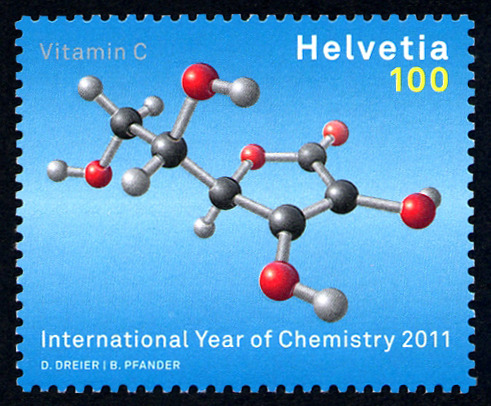

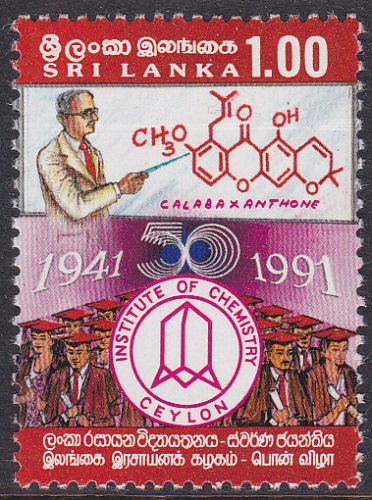

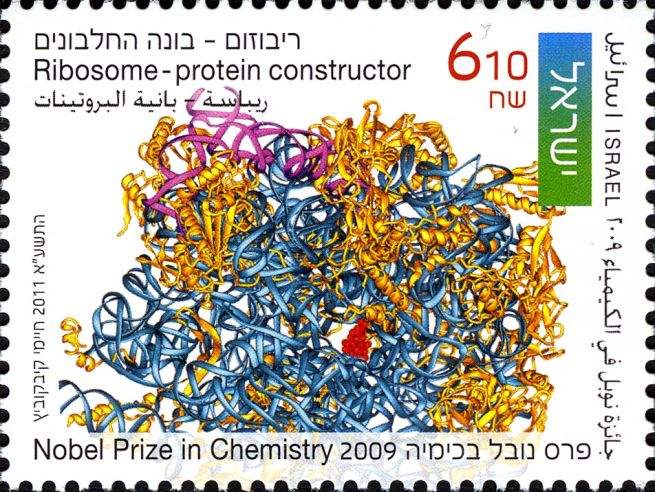

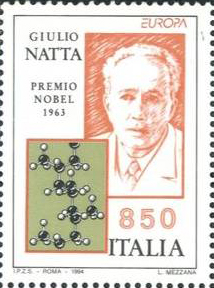

Inorganic structures on stamps are few in number. Structures of organic compounds are much more numerous and diverse. They present hydrocarbons (benzene is most popular) (7) – (9), naturally occurring compounds – quinine (10), penicillin (11), many others (12) – (15), complex biochemical structures – DNA, proteins (16), etc. Polymers – both natural and synthetic ones – play an increasing role in our life, and, of course, they deserve to be shown on stamps – see (17), (18).

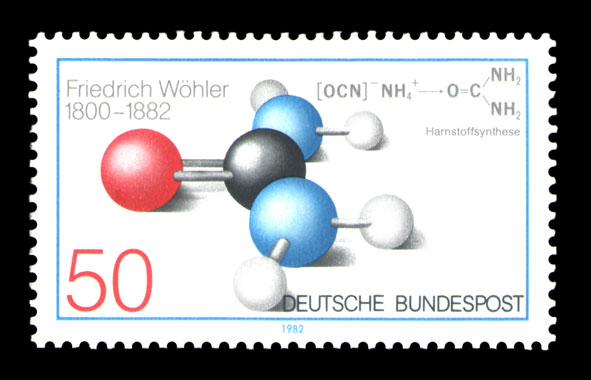

The direct relationship between organic and inorganic compounds was demonstrated in 1828 by a German chemist Friedrich Wöhler who is believed to be a “father” of organic chemistry. The German stamp (19) shows the equation of the Wöhler synthesis of urea from ammonium cyanate.

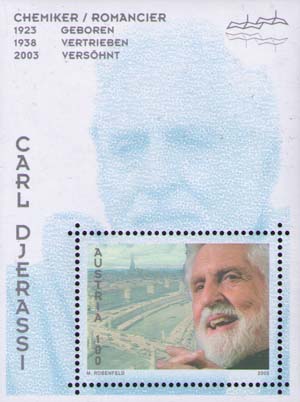

Many organic compounds contain stereo centers and must be drawn with correct stereochemistry. A good example is a 2005 Austrian souvenir sheet that contains a stamp honoring Carl Djerassi (20) – an Austrian-born American chemist. The sheet features his portrait and enantiomeric steroid molecules – with correct stereochemistry. This sheet was the first of its kind in the world: the face in the background was composed of microscopic chemical formulae –enantiomers of the steroid.

In addition to structures and formulas, chemical nomenclature is an important part of chemical language. The history of the present-day nomenclature is counted from the 1892 international conference in Geneva, from which the first widely accepted proposals for standardization arose. The Swiss stamp (21) celebrates the centenary of this event (give a systematic name to the molecule shown on this stamp!).

Philately is not simply a hobby! It is a rapid and efficient way to disseminate information, increase curiosity and attract attention to any specific subject including chemistry. In this respect, chemical mistakes deserve special attention. In philately, mistakes are not rare – both in the stamp design and in printing. The reason for the former is simple: the designers are not chemists, neither are the postal service officials, and sometimes they do not check the stamps carefully. Printing errors are always welcome by stamp collectors because such errors make stamps more rare and, hence, more expensive. For example, the inverted overprint on a stamp can increase its value by many thousands of times. Chemistry mistakes are interesting more from an educational point of view – it is always fun to discover the mistake and to discuss its origin. Please, find the mistakes on the stamps (22) – (25) (some are obvious, others are not).

And the final comment: no stamps have been devoted to chemistry Olympiads yet. Mathematics and physics were more lucky in this respect – see (26) and (27). We tried to issue a Russian stamp devoted to IChO-2013 but failed due to bureaucratic barriers. Waiting in the future!

Exercise. What molecules are shown on stamps (9), (12-15), (17-18), (20), (24)? What are they used for?

For more on the topic:

1) Z. Rappoport. Chemistry on stamps (chemophilately). // Acc. Chem. Research, 1992, v. 25, no. 1, pp. 25-34.

2) E. Heilbronner, F.A. Miller. A Philatelic Ramble through Chemistry. – Wiley, 2004, 268 p.

3) S.L. Rovner. Chemophilately. // Chem. Eng. News, 2007, v. 85, no. 51, pp. 29-31.

Vadim Eremin,

Chemistry Professor, Moscow State University

(1) Great Britain 1977

(2) Uruguay 2011

(3) Sri Lanka, 2011

(4) Slovakia 2011

(5) Great Britain 2001

(6) Soviet Union 1968

(7) GDR, 1979

(8) Korea, 2006

(9) Czechoslovakia, 1966

(10) Cuba, 1962

(11) Hungary, 1981

(12) Great Britain, 1977

(13) Switzerland, 2011

(14) Soviet Union, 1968

(15) Sri Lanka, 1991

(16) Israel, 2011

(17) Italy, 1994

(18) Germany, 1971

(19) Germany, 1982

(20) Austria, 2005

(21) Switzerland, 1992

(22) Mexico, 1973

(23) Monaco, 1986

(24) USA 2008

(25) Soviet Union, 1962

(26) Korea, IMO-2000

(27) Iran, IPhO-2007

Автор - профессор В.В.Еремин (химический факультет МГУ, для журнала "Catalyzer" 45 МХО).

интересная статья,

интересная статья, ,

,